ABOVE IMAGE: Master of Frankfurt and Workshop, The Adoration of the Magi with Emperor Frederick III and Emperor Maximilian, 1510–20. Oil on panel. © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp.

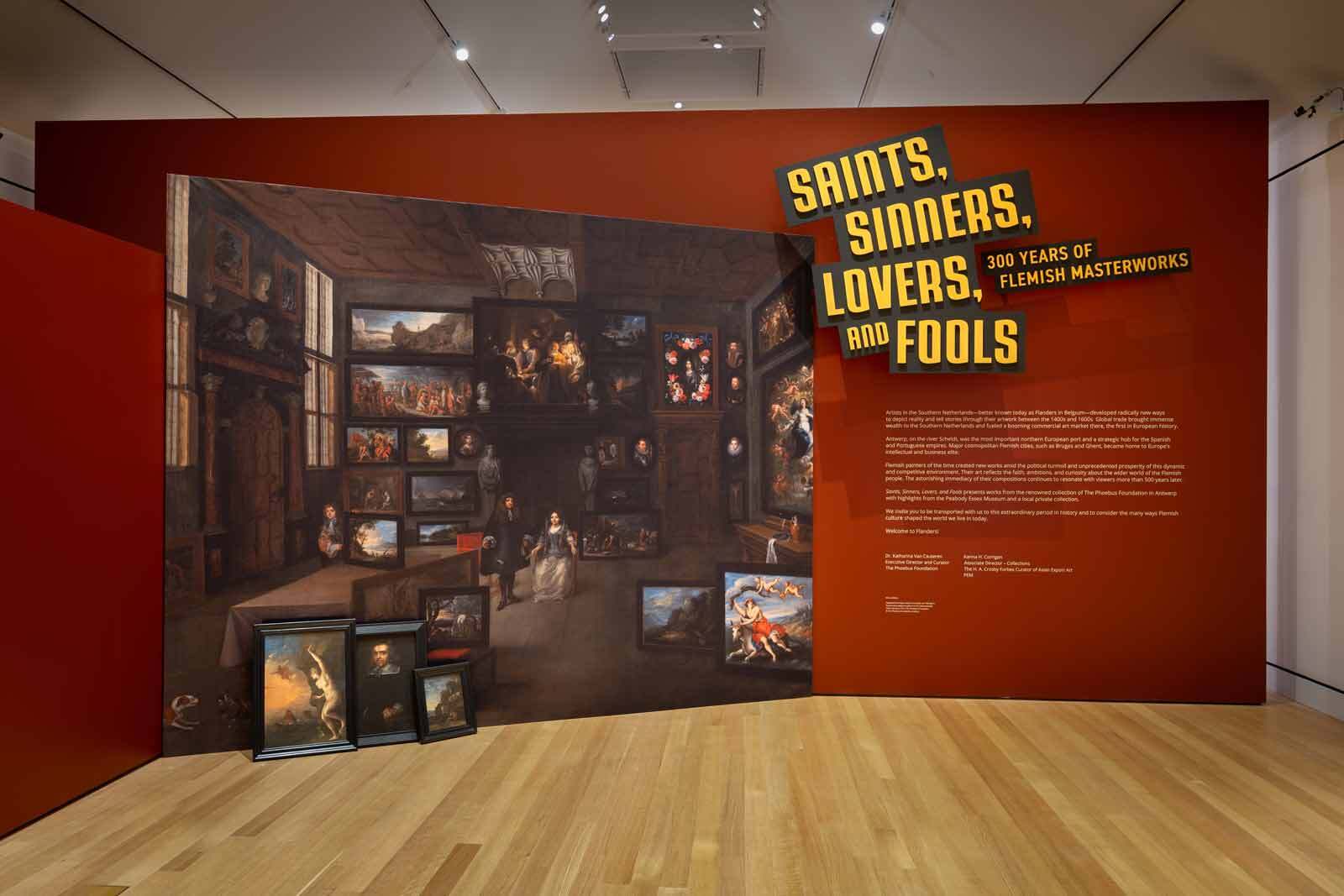

The opening of Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks, a traveling exhibition co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and The Phoebus Foundation, is just a few days away on December 14. PEM’s Ellen and Stephen Hoffman Curatorial Intern Lucy Montgomery reflects on her experience researching and reviewing materials for the exhibition this past summer.

From the moment I arrived at PEM, I was thrown into editorial deadlines for Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks. During my ten-week internship, I was included in the lengthy but exciting process of helping bring an exhibition to fruition, from drafting the exhibition script to arranging objects for display.

During my time as an intern last summer, I delved into Flemish and Dutch art history to get better acquainted with the luxurious works on display. First, I helped compile the tombstones (the basic information displayed about each piece, including artist’s name, title and medium) for the exhibition. This helped us to conceptualize the story and flow of information to answer key questions: How can we arrange these works to best convey a specific time and a place — in this case, 15th–17th -century Flanders?

Artist in the Southern Netherlands, Portrait of a Woman, 1613. Oil on panel. © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp.

How can viewers be immersed in a tavern or chapel from hundreds of years ago while walking through PEM’s galleries? Eventually, these tombstones formed the foundation of the full exhibition script, along with additional images of every piece and introductory text for each thematic section in the gallery.

Artist in the Southern Netherlands, Portrait of a Woman, 1613. Oil on panel. © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp.

This traveling exhibition, mostly composed of works from The Phoebus Foundation, is augmented by PEM objects in a recreation of a cabinet of curiosities — or wünderkammer, a collecting practice of the European elite. Curator Karina Corrigan and I visited PEM “curiosities” in storage to determine their medium and measurements. In temporarily closed-off gallery space, we were even able to place objects in true-to-size mockup cabinets and arrange them to recreate the dazzling effect of a true wünderkammer. Handling objects directly can be a rare experience for curators (much less interns!), but we had the privilege during our intense wünderkammer design process.

An early version of the exhibition’s wünderkammer. Photo by Lucy Montgomery/PEM.

One complication was finding a way to showcase PEM’s taxidermied ostrich. Does a huge, preserved bird from before 1922 need a full display case? (Hint: yes, it does. The arsenic used in historic taxidermy makes it a potential health hazard.)

An early version of the exhibition’s wünderkammer. Photo by Lucy Montgomery/PEM.

I joined Karina in numerous exhibition planning and design meetings and reviewed dozens of floor plans and 3D digital renderings of the gallery space. Working closely with PEM’s Exhibition Design team, we carefully determined the position of each painting, sculpture, object and text panel to guide visitors through a cohesive story. I learned how every panel and placement can shape the trajectory of an exhibition.

Design meetings led to conversations about how to evoke a mood in each room using paint colors, interactive activities and the shape of the walls. For example, what makes a gallery of religious art feel like a chapel or devotional space? How can the physical elements of the room, such as ceiling beams, be used to evoke a serene and sacred environment?

The Catholic Church was a cornerstone of many Flemish people’s lives during the period the exhibition covers, which is particularly evident in Pieter Coecke van Aelst’s painting Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi. The Adoration, when three wise men brought gifts for the infant Jesus, resonated deeply with the emerging merchant class in Antwerp. With its inherent focus on foreign luxuries and glamorous wealth, the Adoration would have spoken to many in Antwerp who devoted their lives to international trade and long-distance travel. Coecke van Aelst’s own commercial success as a painter and tapestry designer for Europe’s elite resulted in an exciting life for the time. He traveled as far as Constantinople (now Istanbul) in 1533 to plan a costly tapestry for Süleyman the Magnificent, as well as to Italy, where he was influenced by Renaissance painting techniques.

Biblical commentators in the 16th century suggested the wise men, or Magi, were three kings representing the three continents known to Western scholars’ narrow view at the time: Europe, Asia, and Africa. In Coecke van Aelst’s altarpiece, Melchior, meant to represent Asia, wears a headdress almost certainly inspired by the artist’s travels to Constantinople. Figures in his travel prints wear strikingly similar clothing.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Mayken Verhulst, Customs and Fashions of the Turks (Ces Moeurs et fachons de faire de Turcz) (detail), 16th century. Woodcuts in a frieze of ten blocks printed on ten sheets. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928. 28.85.1-.7a, b. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Licensed under the CC0 1.0 Universal License.

Coecke van Aelst and his workshop also kept up with new painting trends. The background landscape that unrolls continuously across all three panels was a break with tradition at the time. The artist’s experience designing tapestries meant for immense halls and palaces must have influenced the expansive landscapes and complex compositions in his small domestic altarpieces. This work highlights how depictions of religious and mythological scenes combine with an artist’s understanding of the world to reflect a specific time and place.

Pieter Coecke van Aelst and Mayken Verhulst, Customs and Fashions of the Turks (Ces Moeurs et fachons de faire de Turcz) (detail), 16th century. Woodcuts in a frieze of ten blocks printed on ten sheets. Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1928. 28.85.1-.7a, b. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Licensed under the CC0 1.0 Universal License.

Of all the magnificent altarpieces in the exhibition, Triptych with the Adoration of the Magi demonstrates the foundational content of the show: the burgeoning middle class, the intense cultural influence of Christianity and globalization and the new revelations and innovations of the time. Coecke van Aelst’s aesthetic decisions in Triptych with the Adoration – such as the extravagant costumes, dynamic figure poses, startling colors and gold ornamentation – recall the rapidly growing prosperity of Flanders.

Peter Paul Rubens, A Sailor and a Woman Embracing, 1615–18. Oil on panel. © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp.

Just like this painting, at PEM, so many more elements come into play behind the scenes than I previously thought. The complexity of this exhibition allowed me to consider a world far beyond the here and now. My curatorial internship gave me a peek into both 16th-century Flanders, and the wide world of the inner workings of a museum.

Peter Paul Rubens, A Sailor and a Woman Embracing, 1615–18. Oil on panel. © The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp.

Saints, Sinners, Lovers, and Fools: 300 Years of Flemish Masterworks is co-organized by the Denver Art Museum and The Phoebus Foundation, Antwerp, Belgium. This exhibition at PEM is made possible by the Richard C. von Hess Foundation, The Lee and Juliet Folger Fund, the Samuel H. Kress Foundation, and Carolyn and Peter S. Lynch and The Lynch Foundation. We thank Jennifer and Andrew Borggaard, James B. and Mary Lou Hawkes, Chip and Susan Robie, and Timothy T. Hilton as supporters of the Exhibition Innovation Fund. We also recognize the generosity of the East India Marine Associates of the Peabody Essex Museum.

The exhibition is on view until May 4, 2025.

Keep exploring

Blog

Object spotlight: A family story behind Black Election Day and a portrait at PEM

5 Min read

Blog

A conversation with the curators of “Ethiopia at the Crossroads”

10 Min read

Blog

Korean art and music comes to PEM

5 Min read

Blog

Object Spotlight: The Belle o’ the Ball Hoop

5 min read