Shoes: Pleasure and Pain is a magnificent exhibit of over 300 pairs of dazzling footwear.

For this month’s PEM/PM event, scheduled for December 15, we dove into our ephemera collections for advertisements, images, and trade catalogs chronicling the history of shoe manufacturing.

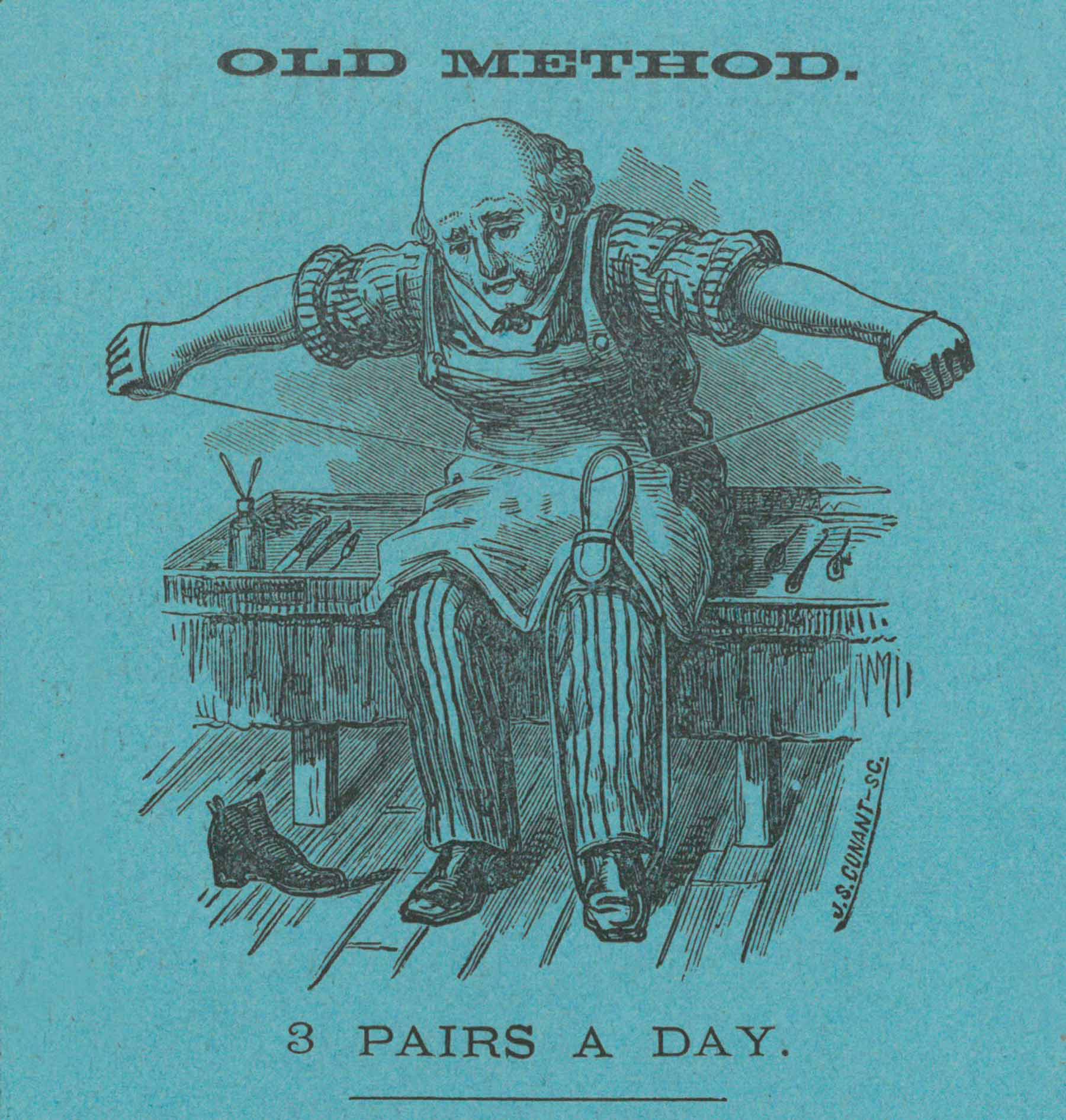

Prior to the Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), shoe manufacturing was an entirely hand-made business. Professional cobblers worked out of their homes. While for many, making shoes provided their primary source of income, for others it was a means of supplementing their earnings from other work (i.e. fishing or farming). Cobbling was a family business, and many male shoemakers were supported by the women in their households who were often responsible for binding the upper part of the shoe.[1]

From the catalog for Goodyear Machine-Sewed Welted Shoes.

Lynn, always an integral location for shoe manufacturing in Massachusetts, became known as The Shoe City at the turn of the nineteenth century. With the technological advances as a result of the Industrial Revolution, Lynn experienced an increase in urban development and factories.

“The Shoe City March," cover to sheet music by Herbert Walker.

Through the automation available from mechanized processes, shoemakers leapt from making five shoes per day, to fifty pairs. The increase in production dropped the price for the consumer and, subsequently, the rate for wage workers. Tensions came to a head in the late 1850’s when Lynn workers began to organize in an effort to pressure employers to increase and standardize the wage rate.

After months of planning, the strike began on George Washington’s birthday: February 22, 1860. The strike gained national attention when female factory workers, and the few still working at home, also joined the strike. Presidential candidate Abraham Lincoln said of the issue, “I am glad to see that a system of labor prevails in New England under which laborers can strike when they want to, where they are not obliged to labor whether you pay them or not. I like a system which lets a man quit when he wants to, and wish it might prevail everywhere.”[2] Unfortunately, despite the national attention, the strike was largely unsuccessful and the laborer’s abandoned the strike within a couple of months.

In 1885, Lynn resident Jan Matzeliger, a Dutch immigrant from Africa, debuted his Lasting Machine which completed the mechanization capabilities of factories and obliterated the need for any at-home cobblers.

With the Lasting Machine, factories surged in productivity, making up to 750 pairs of shoes per day.[3] For more information on Matzeliger’s extraordinary life, see his personal papers, on deposit at the Phillips Library from the Lynn Museum and Historical Society.

[1] “1860 Showmakers Strike in Lynn.” 1860 Showmakers Strike in Lynn. Massachusetts AFL-CIO. http://www.massaflcio.org/1860....

[2] Ibid.

[3] Herwick, Edgar B., III. “How Lynn Became The Shoe Capitol Of The World.” WGBH News. http://news.wgbh.org/post/how-....

Keep exploring

Collection

American Art

Past Exhibition

Shoes: Pleasure and Pain

November 19, 2016 to March 12, 2017

Blog

PEM shoe collection inspires designers

6 min read

Historic Houses

Lye-Tapley Shoe Shop

Built in 1783

0.1 miles from PEM