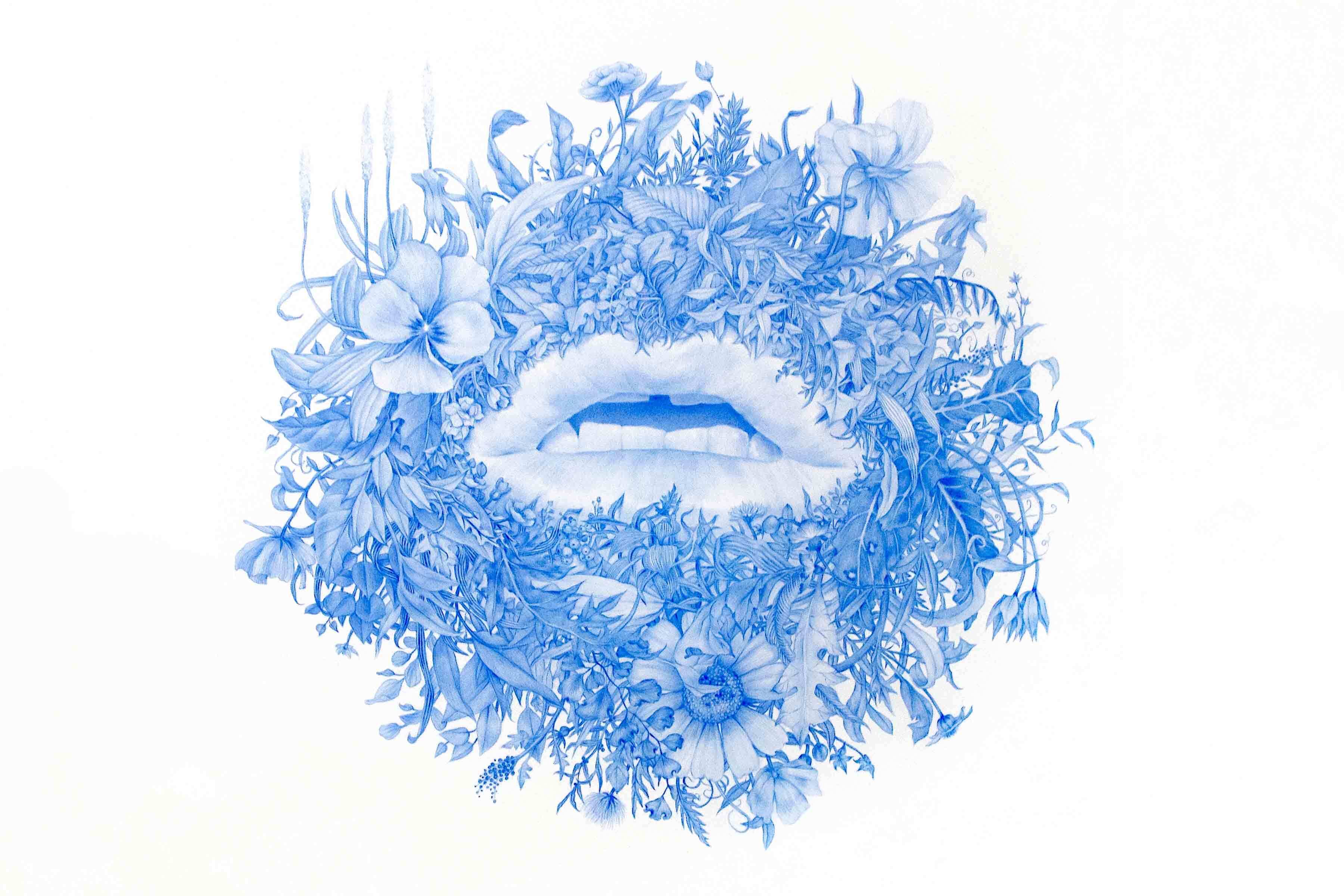

TOP IMAGE: Zachari Logan, Mouth no. 3 (detail), from Wildman Series, 2019. Blue pencil on mylar. Courtesy of the artist.

In Episode 27 of the PEMcast, we explore themes of love and loss.

This is a big topic — may be the understatement of the year — and so we have decided to split into Part 1 and Part 2. In the first installment, we introduce listeners to Canadian artist Zachari Logan, whose provocative botanical drawings of flowers in various states of transformation speak to the power of loss. And remind us that a weed sometimes is so much more than a weed. We begin the episode by listening in on a conversation recorded between me and my Dad. As he was dying in 2015, he offered advice for a happy life.

We then switch to Logan installing his work in the exhibition Zachari Logan: Remembrance and hear him drawing onto the gallery walls. These works explore nature and ideas of the artist’s mortality and sexuality. “There's no separation between the landscape and the human body,” he says. “We're one and the same. What we do to the landscape, we do to ourselves.”

Remembrance offers a place to contemplate loss – caused by the pandemic, war, mass shootings, changing laws about our bodies. But the flipside of loss, as art often reminds us – is love. Visitors are leaving messages of remembrance in a digital logbook. You can leave one at pem.org/remembrance.

Here are snippets from a few:

– “Miss you every single day. Hope you’re dancing the night away with Grandpa Clyde.”

– “Your ashes were spread at the lake last week.”

– “Every beauty in nature that you appreciated in life is now in bloom and celebrating you while you rest.”

For Logan, plants contain multitudes and they have their own language to decode. He finds parallels between the ways in which people in our society talk about plants and how they talk about differences in sexuality. “Some plants are considered useful, and some plants discardables,” he says.

Zachari Logan, Wreath, Silhouette, 2016. Pastel on black paper. Courtesy of the Artist and Alan Avery Art Company. ATL.

“These are the only representations of plants and flowers that have ever made me want to cry, and that's Zachari's work in general,” says exhibition curator Siddhartha V. Shah, Director of Education and Civic Engagement and the Curator of South Asian Art. “There's so much emotion in his drawing and in his paintings. There's something intangible to me about what might draw us to his work. Art historians, curators, tend to have a lot of language for art. It's what we're skilled at, but when it comes to Zachari's work, I'm at a loss for words because it's something that's felt in the heart.”

When the exhibition opened in May, we offered a public workshop inviting people to write their own eulogy. The facilitator was Peyton Pugmire, a dynamic force who offers creative workshops to help people live in their truth. For the episode, we paid a visit to Peyton in his studio in Marblehead. Turns out writing our own eulogy presents the opportunity to forge a new relationship with death, and see it as a source of inspiration for the present. “How do we want to show up now and live?” asks Peyton.

Indeed.

We end the episode at Salem’s recent Pride Parade, celebrating life, and the chance to live it to the fullest.

Zachari Logan: Remembrance is on view at PEM through May 7, 2023. Join those who have left a heartfelt message of remembrance for a loved one at pem.org/remembrance. Zachari Logan’s collection of poems, A Natural History of Unnatural Things, is sold in the Museum Shop. Thanks for listening. This episode of the PEMcast was produced by me, Dinah Cardin, and edited and mixed by Perry Hallinan. The PEMcast is generously supported by the George S. Parker Fund. Stay tuned for Part 2 of Love and Loss when we’ll explore the brief creative life of fashion designer Patrick Kelly, now being celebrated at PEM. This queer, Black designer struggled for racial equality and changed fashion forever before his life ended on January 1, 1990.

A local bartender enjoying Salem Pride. Photo by Amy Brooks/PEM.

PEMcast Episode 27: Love and Loss (Part 1)

[Classical music]

[Bird sound]

[Man laughing]

Dinah's Dad: That bird is just determined isn’t it. I wonder how many babies they have? Just one or more?

Dinah: Why does the bird like your voice so much?

Dad: I don’t know.

Dinah: I’m going to show you this picture. How old do you think you are there?

Dad: I was 40.

Dinah: My age… Your hair was kind of dark.

Dad: It was. Amazing.

Dinah: You can see the tape on the photo. It’s like another lifetime isn’t it?

Dad: It was another lifetime.

Dinah: This is my dad in 2015 when he was suffering with Stage 4 cancer.

Dinah: What wisdom would you give me? I’m 40 now. What do you think is the most important thing to remember?

Dad: To live life to the fullest.

Dinah: And how do you think one does that?

Dad: Be nice to yourself.

Dinah: That’s good advice. That’s really good advice.

Dad: Well I’m ready to go in, babe.

Dinah: OK.

Dad: It’s getting dark.

[Clicking of recording]

[Camera clicking]

Host, Dinah Cardin: I’m standing in a museum gallery. And every six seconds I hear a click. Though it sounds like it’s counting off the minutes and seconds of my life, it's actually a camera. Shooting a time lapse of Zachari Logan drawing on the walls.

Zachari Logan: Yeah. It's crazy. That’s why I had my music on. it started to get louder and louder and louder. A thread that runs through my work is just my own acceptance of my mortality, as just a fact of my life.

Dinah: Welcome to the PEMcast, conversations and stories for the culturally curious. From the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, I’m your host Dinah Cardin. In this episode – the first of two parts– we look at love and loss. Pandemic, mass shootings, war, rapidly changing laws about our bodies. Lately, much of our experience of the world is colored by loss. But, as art and artists continually remind us: the flip side of loss is love. Today we explore the museum’s meditation gallery which features Zachari Logan’s new exhibition. He takes us deep into our grief so that the light may shine brighter. We’ll also talk with an arts therapist who helps us write our own eulogy. And work backwards to live life in our deepest truth.

[Marching band sound and cheering]

Dinah: And finally, we take you to our Pride Parade on the streets of Salem. So, let’s jump back in with Zachari Logan.

Zachari: My name is Zachari Logan. I'm based in Regina, Saskatchewan, in Canada.

Dinah: Zachari’s work has been exhibited in Paris, London, Brussels.

Zachari: I work primarily in large scale drawing…primarily pastel, blue and red pencil on Mylar. I also work a lot in ceramics. We've brought together a number of works that, for me, are about exploring ideas of my own mortality…and a host of other issues related to sexuality and ecology.

Dinah: The exhibition consists mostly of organic botanical drawings. But like lots of Zachari Logan’s work, it’s also about his body.

Zachari: There's no separation between the landscape and the human body. We're one and the same. What we do to the landscape we do to ourselves. That's also reflective of a pandemic that is likely caused by encroachment. Thinking about what we've come through, but also perhaps potential hope for the future in terms of how we might learn from what's happened. I'd like to slow the viewer down and have them reflect on their own experience of what happened since the pandemic began.

[Sound of drawing]

Dinah: Those are so delicate.

Zachari:This is a hard angle for me because I’m trying not to smudge. I love flowers as they're transforming. I love them when they're "fresh cut flowers," but I also love them as they are slowly decaying and changing color and changing texture. Trying to capture that in a drawing is very meaningful to me. The acceptance of that in one's own reality, in their own body, is difficult and it's not like one day you wake up and you're like, "Cool. I'm going to die. Done."

Dinah: What's the name of the plant?

Zachari: I don't know because. These are combinations of forms so none of these come from any observation, other than past observations. I would call that muscle memory.

Dinah: This organic feeling solo exhibition is called Remembrance. These exquisite drawings mix the wild and the cultivated, the strange and the familiar to immerse us in a field of beauty and desire that celebrates the natural world.

Zachari: I'm going to take a bit of this plant and a bit of this plant. So they are taken out of a memory bank in my brain and probably at some point came from an actual form of a flower. It's always different every time you conjure it, right? I just decide that I feel that it looks right and then I move on to the next one. [laughs].

Dinah: I love the wispy little roots even, of something that looks almost like it's dried and blowing away.

Zachari: Yes, that’s exactly what I wanted, so yeah. I’m glad you mentioned that.

Dinah: The ephemeral.

Zachari: There's a sense of whimsy abstraction like air flowing, dreamlike, surreal, all of that sort of thing.

Dinah: It's like you're creating a dreamy world.

Zachari: In many ways, the plants are stand ins for my own body or the body.

Dinah: Zachari’s work always includes his body, even when it’s not figuratively drawn. The materials he’s using can play a part. Ceramic as bone, paper or Mylar as skin. He even found inspiration during the strictest time of lockdown, from a studio accident.

Zachari: I’d had a very unfortunate injury on my thigh. I got a bad bruise from dropping a box of clay on it. I started recording the colors of the bruise as it shifted over time as a representation of time passing. The drawing Bruising is essentially the mapping of that bruise through the colors represented in the dried flowers. It really is a representation of time. That sense of time is just bizarre. [laughs]

[Sound of drawing]

Dinah: So, how do you feel about the fact that this will be potentially painted over for the next show?

Zachari: That is the intention behind the work. Here as a gesture then it's gone no differently than any of us. [laughs] We have whatever our timeline is and then it's, then it’s done.

[Music]

Dinah: Why did you bring this exhibition to us?

Siddhartha Shaw: Before this exhibition was here, we had Zarah Hussain: Breath and that was in response to the pandemic and other challenges of 2020 that we were dealing with. Given that we’ve all experienced so much loss in the last couple of years, loss of lives, loss of time, this seemed like a really special and timely project to follow up on that. So that project was a meditation on the breath and the passage of time and this is a medication on loss. That was I'm Siddhartha V. Shah. I'm the Director of Education and Civic Engagement and the curator of South Asian Art, and also the curator of this exhibition. I truly believe that reentry is the one of the most challenging aspects of anything that we go through. I think we need to stay with this a little longer.

Dinah: So this helps us process?

Siddartha: It's a little bit like if the heart is bleeding, I'm speaking metaphorically or if the heart is broken because of a loved one who has died, we can't just put the heart back together again. Sometimes the heart has to learn to live with heartbreak. Sometimes the heart has to live and move on while it continues to bleed. When there is loss, it's a very human impulse to move towards pleasure and away from pain. To grieve consciously means to say yes to that experience, the reality of what is happening.

Dinah: We’re looking at a large scale drawing that is a silhouette of a wreath. A circle with no beginning or end, it symbolizes eternal life and the indestructible spirit even after death.

Zachari: Wreaths have been for many, many generations been put at in funerals, on graves as a memorial, as a commemoration, but they're historically were put on the heads of athletes when they won competitions. And so, they're celebratory as well. They have been featured in neoclassical paintings.

Dinah: Why do these look like they're in relief? Negatives?

Zachari: The paper itself is considered to be black, this is black paper. But of course, the pastel punches a hole into another dimension. When you put the black pastel onto the black paper, the black paper just looks silvery. And it picks up light in a way that differences the light form the material enough to create this.

Dinah: Why is something so absent of color so beautiful?

[Laughter]

Zachari: For me, I look at a piece like this that I've done, I see a lot of depth in it. Even though it is simply this black pool. When I look at Victorian silhouettes of figures, a side profile of children. It was really delicately made. I don't know if you've seen them. They're exquisite, they feel really dimensional. They're also incredibly ghostly.

Dinah: Zachari is obsessed with darkness, shadows, the morbid, the Victorian. It’s perfect for an exhibition in Salem. A nocturn over a body of moonlit water features a disembodied hand emerging from the shrubs and poking a finger into the ground.

Zachari: A lot of people look at the hand and think because of the composition and the way it's emerging, it's sort of cadaverous. It does have that weight, perhaps.

Siddhartha: So, Seeding Number Two is a work that, to me, speaks a lot about hope. Not so much about conscious grief, but it does have a dark vibe to it. There's a very dark night sky. It feels kind of ominous. It feels tumultuous and turbulent. It's not the most happy and uplifting image when you first look at it, but that hand and that finger is planting a seed. It's a gesture of planting a seed of hope even in this rocky landscape you see there.

Zachari: It is supposed to be in a way an image of hope, but it's a nocturne. It’s sort of almost looking that hte hand could be coming from the underground. Why is is stretching like this? Those are all questions that a drawing can ask that it can't answer really, necessarily. I don't think I would want to. Other than to say I like ambiguity. And I think there's a lot of ambiguity in life, and I think there's a lot of ambiguity just in viewing things at nighttime, like "Did I see that?" "Were those glowing eyes?" "Was that a coyote?" Your eyes play tricks on you in the nocturne. That's one of the reasons why a lot of my works, I have an interest in darkness, in nighttime scenes.

Dinah: A similarly dark work features a flower referenced in a short story by Salem’s own Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Zachari: yeah, actually that particular flower is called the Datura which is my number one favorite flower in the world. I don’t know if you know anything about Datura, but they are incredibly poisonous to humans. I just sort of found them at my local farmers market one day, I loved the leaves. I didn't even know about the bloom. The woman who was selling them said, "Oh, if you like the leaves you're going to love the bloom, it blooms this beautiful trumpet." They are also incredibly beautiful. They only bloom at night. In the daytime they sort of dilapidate in the heat of the sun. They're very magical. They also have a long history of being used by indigenous peoples for different purposes.

Dinah: For Zachari, plants contain multitudes and they have their own language to decode.

Zachari: I find parallels between the ways in which people in our society discuss plants or talk about plants or articulate plants and how they talk about, for example, a difference in sexuality. Some plants are useful, and some plants are discardables. To think about queerness, and living in a place like Saskatchewan that can be a little marginal for certain peoples. And I started thinking about the weeds as sort of stand ins. Where the weeds are, which are in the ditches along the sides of the roads, and that sort of liminal space being a queer space on the prairies, and the weeds being stand ins for queer bodies or othered people. Why is a weed a weed? It's deemed a weed because it has no use for human consumption, but it still has a very real purpose and a need to live and to thrive.

Siddhartha: These are the only representations of plants and flowers that have ever made me want to cry, and that's Zachary's work in general. He's a very tall person. His work takes on the form of a body, and so I'm moved by that, the way that plants represent the body in his work. I'm also drawn to the precision in his work. I'm drawn to figurative, and I'm drawn to tiny, tiny details, but it's the incredible detail in his work that inspires me. There's so much emotion in his drawing and in his paintings. There's something intangible to me about what might draw us to his work. Art historians, or curators, tend to have a lot of language for art. It's what we're skilled at, but when it comes to Zachari's work, I'm at a loss for words because it's something that's felt in the heart.

Zachari: Initially it was that I didn't see myself reflected in art history, which was a language that I was very interested in. I also was raised Roman Catholic and I had all these images of male bodies in different states of nudity and violence. I was just available. I was there. I could use myself as a model, and I am a queer contemporary person so there was a way for me to access an agency there. My idea of queer embodiment relates to that idea of body as land. For me, a queering of my body visually is that integration, that idea of yes, at some point my body is going to be food for the trees.

[Music and sound of rain]

Peyton Pugmire: Death is something that, keeping the focus on myself, I have fears around. My fears mostly involve around feeling pain at the end of my life. It's not so much about leaving this life, although I do have some anxieties and fears about exiting this costume and this personality… letting go of Peyton Pugmire.

Dinah: This is Peyton Pugmire.

Peyton: I'm the founder and owner of a small business called Creative Spirit, which is based in Marblehead, Massachusetts. I'm just all about helping to foster one's creativity and personal transformation.

Dinah: I feel as though we're tapping into personal transformation right now because we're sitting on the floor, and this beautiful large rug, and what happens in this space normally?

Peyton: I’m currently focusing here on my spiritual, intuitive readings or counseling with my clients. I also do past life regression hypnotherapy.

Dinah: We recently offered a program to pen your own eulogy.

Peyton: The word "death" brings up a lot of stuff. It's a loaded little word. Writing our eulogy as an exercise, to me, is a way to reflect on how to live a fully expressed life. In that process of writing our eulogy, when we are healthy and capable of living on for as long as we can, we're able to imagine the end of our life, which, of course, is inevitable. This workshop invites us into the opportunity to forge maybe a new relationship with death, and see it as a source of inspiration for the present. Again, how do we want to show up now and live?

Dinah: This exercise allows us to rewind the tape and live our lives according to this document we have written about ourselves.

Peyton: I know that when I lost my father a couple of years ago, I learned afterwards that my father and my mom did not talk about his death. They didn't talk about it, they didn’t plan for it. My understanding of the reason why is because they were just both so afraid. They weren't ready to look at that. And I understand that.

Dinah: Queering Death, exploring beyond the stigmas, stereotypes and taboos of the inevitable end of our lives. As is the natural death movement. To no longer put people in thick makeup and bury them in fancy boxes. To offer agency for more creativity, a green burial, a more natural goodbye.

Peyton: If sitting solo in your home thinking about the world without you in it physically, if that is overwhelming, do it with a friend so that you can sit in that support. Your friend can also jog your memory about your beautiful self, right, your goals and your legacy that you want to leave behind. When you finish your eulogy, light a candle, gather some beautiful flowers, and have a friend read you your eulogy, and sit in the presence of your own words and in your feelings as it's being read to you. I also coach people on how to develop their intuition, which is your inner voice, guiding you softly, gently, and lovingly on how to navigate your life authentically, positively, and safely.

Dinah: Peyton encourages people to use this inner intuition, their inner GPS, to step into the light of their own truth.

Peyton: As a child, I was always in my imagination. That was the world in which I existed most happily. And then in 1998, I came out of the closet as a gay man, and that galvanized my life and my sense of purpose because my coming out, on a macro symbolic level, that was me standing in my full truth to say, "Hey, world, this is who I am, and this is what I'm going to do." I'm going to continue until I die to stand in my truth, wave my freak flag, and to always follow my dreams.

Dinah: Peyton says that when we come out and stand in our truth, it’s like we become superhuman. "Oh, my gosh, I'm still alive." Not only am I still living, but I'm thriving, and I am in my dream supported by my God, supported by my loved ones, my family, and friends. Now, I know that's not always the case for everyone, but there is support always somewhere, even if it's from Mother Earth, who's always got our back and ourself.

Dinah: We all have truths that are hard to own, says Peyton, or difficult to express.

Peyton: So, ever since then I’ve been obsessed with coming out in every regard possible. I believe that all of us, regardless if you identify as a person on the LGBTQIA spectrum, we all come out, and we all can come out. Coming out with feelings or coming out with a new career idea, or even an artist who's created what they feel in their heart is their masterpiece. All of that to me is coming out, coming out of the closet. Coming out of the closet of secrecy and fear to stand in the light and say, "Here is who I am. Let the light on all of me, and please see me."

Zachari: Things to remember when I die.

Dinah: This is Zachari Logan, reading a poem from his collection.

Zachari:

Put me back in the ground

where I came up.

The garden of skin.

Bury me in the backyard

with the cats.

Keep me from

the masochistic whispers

of graveyard sainthood.

Out of sight of watchful cobblestone glances.

Grace I want nothing to do with.

Every now and then

Spill some coffee

into the earth for me.

An offering to an atheist.

The green blanket

six feet above, a receptor

for every salutation,

folding like dampened paper.

Years of forgetfulness.

Fathoms of poetic decay.

No miracles -

I plan to stay where I am,

a Lazarus for the twenty-first century.

Until one day someone

buries this poem

in the ground

and like a nymph

of the groundwater I

pull it to life underneath.

[Camera clicks]

[Sound from Pride Parade]

Dinah: On the day of Salem’s Pride Parade, I stopped by a memorial service for a friend. See, there it is again, our theme, love and loss, it’s everywhere. On a cliff, overlooking the Atlantic on the most perfect summer day, people came together and remembered a beautiful woman named Jen. And then they remembered…to go and live their lives as fully as they possibly can.

[Music from Pride Parade]

Dinah: Zachari Logan: Remembrance is on view at PEM through May 7, 2023. Join those who have left a heartfelt message of remembrance for a loved one. You can leave it at pem.org/remembrance. Zachari Logan’s collection of poems, A Natural History of Unnatural Things, is sold in the PEM Shop. Thanks for listening to the PEMcast. Stay tuned for Part 2 of Love and Loss when we’ll explore the brief creative life of fashion designer Patrick Kelly, now being celebrated at PEM.

Bjorn Amelan: Yes, this is Bjorn speaking. Patrick and I met in 1983. I would say he was probably the most charismatic and immediately seductive, lovable person that I have known.

Dinah: That was Bjorn Amelan, speaking of his dear partner Patrick Kelly, who died of AIDS on January 1, 1990. You’ll hear more from Bjorn in the next episode as we explore Patrick Kelly, Runway of Love. Learn more at pem.org. The PEMcast is generously supported by the George S. Parker Fund.

Keep exploring

PEMcast

PEMcast 27 | Part 2: Love and Loss

33 Min Listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 26: Our Current Climate

32 Min Listen

PEMcast

Following the Thread: PEMcast 30

30 min listen

PEMcast

PEMcast 31: Queerness and Creativity

24 min listen